Next blog: August 9, 2025

|

| Photo by Susan Coventry |

My big birthday present was a boat trip and scrumptious lunch on Lake Monroe and the St. John's River on—you won't believe!—a STERNWHEELER. Below, the boat and the only semi-good shot I got of the many cypress trees we passed en route. A fabulous celebration which also included live music, the singer someone Susie had known for 20+ years! A truly grand celebration, which included Riley and Cassidy running up to the top deck to enjoy the view as we passed under the I-4 & 17/92 bridges, followed by the mainline (Miami-New York) railroad bridge.

~ * ~

From the number of notes I made before tackling the topic of Regency Sub-genres, I could have written four or five times what you see below. It's a challenging topic, and I can only hope I've said enough to clarify the subject for those new to Regency writing, those who simply enjoy reading the genre, and those who know about the so-called Regency only through the Netflix series, Bridgerton. Most of all, I hope this article passes the inspection of long-time Regency authors, no matter what sub-genre they write.

REGENCY FICTION'S MANY SUB-GENRES, Part 1

The basics:

Regency novels are set primarily in England* during a period most Americans recognize as “the Napoleonic Era.” In modern romance fiction, this is interpreted as the years from 1795-1820, ending with the death of George III and his son ascending the throne, his long years of Regency finally coming to an end.

*settings can vary from London to grand country houses, to Scotland, Wales, and Ireland; from Russia to India to the Americas, but the dress, manners, and mores are those of Regency England. [The British, more accurately, call it “the Georgian Era,” as the Regency of Prince George was only a scant ten years (1811-1820)]

Many readers of our time prefer the Historical novels set in the Regency Era because, although women were still strictly bound by male dominance, they tended to have far more sparkle, initiative, and free-thinking than the poor women later in the century who became totally ensnared in the restrictive life of Victorian times. A period into which my own grandparents were born, and which was still negatively influencing women when I was born, well into the 20th century. I make no secret of my feelings: Victoria’s influence harmed women, and it was not until the 1920s that women finally rebelled, cutting off their hair, raising their hemlines to their knees, and basically saying, “Let ‘er rip!”

I set my first book, The Sometime Bride, in the Regency Era, partly because I loved the novels of Georgette Heyer, and partly because they inspired me to read about the war “on the Peninsula,” which Heyer mentioned occasionally but almost never used in her plots. When I discovered how important this war in Spain and Portugal was in the fight against Napoleon, I knew I had to incorporate it into my writing. Lo and behold, The Sometime Bride and Tarleton’s Wife.

To make a long story short, I ended up writing books set in the Regency for the next thirty-some years. A feat that required the acquisition of shelves of books on myriad topics from the history of the period to what men wore under their tight-fitting pants!

And then, after many years of smugly believing I’d conquered the beast, along comes the TV version of Bridgerton, and I couldn’t help but wonder if the rules of writing Regency were about to be turned topsy-turvy. With only a few exceptions, one of the primary rules of writing Regency has always been authenticity—getting the history, manners, and mores of the times correct. But Netflix’s Bridgerton . . . ! Where did this fanciful version of the Regency Era come from? What author dreamed up this fantasy?

But wait. Julia Quinn, the creator of all those wonderful characters and sparkling dialogue, is a well-known Regency author who follows classic Regency authenticity. Her first book of the Bridgerton series—introducing us to all those amazing characters and with strong dashes of comedy to alleviate the angst of a highly dramatic plot—is an outstanding example of Regency writing at its best. So how did we get the version of Bridgerton seen on our TV screens? I can only assume someone at Netflix decided that if they were going to spend all that money (costumes and scenery alone must have cost a fortune), the Regency needed something “extra”—a re-imagining, of you will. Which would explain why the British upper class in the TV Bridgerton is multi-racial, the country ruled by an autocratic queen instead of the prince who would become George IV. (Yes, the episodes where the naive young queen discovers she has married a man subject to fits of madness was extremely well done, but its outcome was totally re-imagined. The real Queen Charlotte was, according to one expert, “unprepossessing” and thoroughly occupied by presenting King George with fifteen children and by all the problems involved in raising that many royal children.

When the Bridgerton series was wildly successful, as it deserved to be, I couldn’t help but wonder about how it would affect the realistic Regency authors had been striving to re-create since the mid-20th century. What to call this new Sub-genre of the Regency Era? I was particularly anxious, as I am planning to return to Editing and would undoubtedly be faced with manuscripts written by newbie authors who thought the world of TV Bridgerton was reality.

All of which led to my beginning a discussion on the Regency Fiction Writers loop that had Fantasy authors up in arms. My gaffe? I had seen the word “Romantasy” as a sub-genre of Romance and leaped to the conclusion that it was the perfect description for the Bridgerton series. All that verve and sparkle, the gorgeous costumes and settings, the great characters deserved a great new name. Except, oh horrors, the authors of books about fairies and other such ethereal creatures informed me no uncertain terms that Romantasy was only for their version of fantasy, not anyone else’s fanciful view of the world.

Sadly, after more discussion, the only term we could all agree on for Bridgerton, was Alternate History (Alt History), a truly blah term for something as sparklingly brilliant as the Bridgerton series, which is what set me off on a quest for something better, and led to my looking into the many sub-genres of Regency Romance, soon finding myself grinding my teeth. I even consulted a hardcopy of Random House Webster’s College Dictionary, and discovered it has 12 definitions of “fantasy.” I’ve copied the most pertinent below.

1. imagination, esp. when extravagant or unrestrained;

2. the forming of mental images, esp. wondrous or strange fancies; imaginative conceptualizing;

8. an imaginative or fanciful creation; intricate, elaborate, or fanciful design;

9. a form of fiction based on imaginative or fanciful characters and premises;

So . . . could we call Bridgerton “Regency Fantasy”? “Regency Romantic Fantasy?” But then all our Regency novels have some form of Romance. I finally came up with a term that is a pale comparison to “Romantasy,” but sounds far better than the stark term “Alt History.” I would suggest: “Regency Re-imagined.”

Newbies, please note: Being inspired by the TV Bridgerton is great, but before plunging in to write a book based on a television fantasy of the Regency Era, read at least Book 1 of Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton series. Do a little research—learn something about the real Regency before attempting to play with history. I.e., know the true history of the Regency before you re-imagine it.

* * * * *

Next week: my draft list of Regency Sub-genres, with a bit of explanation about each. I invite additions and corrections, as I will eventually share the list with the Regency Fiction Writers e-loop. (The current oracles of everything Regency, as well as an invaluable resource tool for Regency authors. If you want to write Regency, this group is a “must.”)

~ * ~

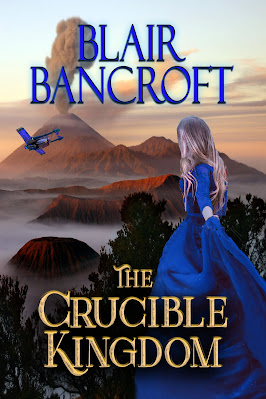

This week's featured book, a different kind of re-imagining—the setting something close to a Medieval court, but in a distant future and a galaxy far, far away.

In this spin-off of the Blue Moon Rising series, the Crucible Kingdom, an obscure planet far, far away, is suffering from an ancient curse—periodic bouts of violent storms, earthquakes, floods, tsunamis, and wildfire. To break the curse, a widowed duchess and a starship captain from the disintegrating Regulon Empire (which her ancestors fled centuries earlier) are forced to work together. Although the duchess grudgingly accepts that the captain is highly capable in emergencies, she scorns the idea that a hard-headed Reg who does not believe in the power of sorcery can be helpful in breaking a curse. And then the captain comes up with an idea no one thought of, setting off a quest that turns out to be more dangerous than the curse itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment